On the 1st of December 2014, Damaturu, the capital of Yobe State, came under attack by Boko Haram insurgents. Six kilometres away in Dikumari, a diverse farming community of 2,000 residents, the gunshots and chaos forced many people to flee the town.

Barely six months later, Dikumari became a host community to some of the nearly two million[1] Internally Displaced Persons (IDP) in northern Nigeria. There are no reliable population statistics, but according to the community’s own estimates there are at least 5,000 permanent residents as well as seasonal visits by Fulani nomads. This increase put the existing infrastructure under strain. For example, there were no medicines at the dilapidated local drug dispensary. The community didn’t have the capacity nor the resources to manage its health facility, and the attendance dropped.

The MNCH2 programme has been working in Dikumari throughout the period of unrest and reconstruction. Since November 2014, the programme has been supporting health services through the renovation and expansion of the health facility and by providing basic equipment. After May 2015, however, the focus has been on accommodating the health needs of the increased population of IDPs and returnees.

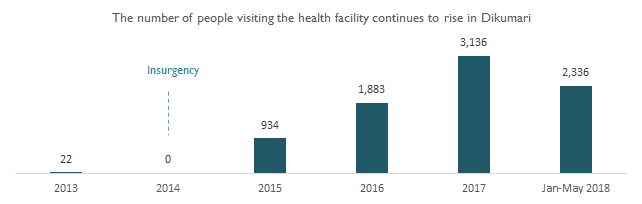

MNCH2 renovated Dikumari’s health facility in 2014. It survived the insurgency and has seen an increasing attendance since then.

Community comes together

A core part of what the MNCH2 does is to strengthen community structures. A Facility Health Committee (FHC) made up of community members was established soon after the insurgency. The Dikumari FHC has stood out in the resolve of its members to mobilise resources to rebuild the community and the broken lives of those who had lost their homes. The FHC members started engaging with some of the demotivated health facility staff to ensure the facility was open when it was supposed to, and that community members receiving services were always treated with respect. By educating the community, women have become more empowered to make choices about their health, especially in terms of Healthy Timing and Spacing of Pregnancy (HTSP). Mohammed Garba, the committee’s Chairman, appreciates the “robust relationship between the health facility and the community […] We meet with the community members to inform them about progress and challenges of the health facility and also discuss their concerns.”

Born pioneers

Both Balki and her baby, who has received all vaccinations, are doing well.

The cominbation of new antenatal, labour and delivery services, and the visible involvement of the community in decision-making through the FHC, has increased the number of women accessing services by almost 150-fold, compared to the pre-insurgency figures. By January 2018, 13 women had given birth with a skilled birth attendant’s support.

One of them was 23-year-old Balki Mohammed. Balki moved to Dikumari after finishing primary school and getting married at 16. She had given birth to her first and the second child at home. But with her husband becoming a member of the FHC, the young mother became the first woman in the town to deliver at the facility: “Although this is my third child, I am proud to be the first woman in this community who attended the antenatal clinic and delivered in the health facility on a new delivery bed! I have made up my mind to mobilise other pregnant women to do the same.”

Source: DHIS2

Read more about how the health of women and girls is part of the healing of conflict-affected communities in the North East.

[1] North-East Nigeria Humanitarian Situation Update. OCHA, February 2018.